How have you been keeping up communication during this period of physical distancing? Have you considered sending letters to your friends and family? In this guest blog, celebrated Brisbane writer David Malouf reflects on the lost art of letter writing.

Corresponding virtues

Nothing in our world of personal relations is more remarkable than the replacement, over the past twenty years, of letter-writing by the quick fire, impermanent forms of e-mail and SMS, with their emphasis on ‘communication’ and immediate but ephemeral ‘contact’.

No more dutiful letters to distant parents. No more extended accounts of recent events or discoveries, no time for speculation or roundabout confession or for qualifications in the matter of opinion and sometimes dangerous prejudice. No further witness to public events, or from those in high places of history in the making— references we might pick up later, and from a distance, as first-hand observations of change or disaster.

From the earliest times—think of Cicero or Seneca or Pliny or St Paul—correspondence made up a large part of how, from a very particular viewpoint, we saw the past, and the more so when the writer was aware, as so many of them were, that they were writing privately and publicly at the same moment, and for that reason carefully managed how what they were setting down would be read and interpreted.

And this self-consciousness was not limited to philosophers and statesmen. Such ordinary correspondents as Madame de Sévigné, in her letters to her daughter, or Lord Chesterton in his letters of advice to his son, were acutely aware that their correspondence would one day bear witness to the world they moved in; not to speak of such later letter-writers as Virginia Woolf and Thomas Mann, or Karen Blixen (the future Isak Dinesen) in her letters from Africa. No wonder, given the play here between self-conscious display and ‘innocent’ revelation, that letter-writing in the epistolary style proved so fruitful in the eighteenth century, in Rousseau’s La nouvelle Héloïse and the novels of Richardson and Smollett, for a new form of fiction, one that offered readers the sophisticated pleasure of a complex and slowly unfolding plot and of eavesdropping, in the most knowing way, on those who did not know, as they ‘wrote’, how much they were giving away.

The decline in letter-writing has resulted in two great losses. The first is the loss, to letter-writers themselves, of the opportunity for slow self-reflection, for re-examination and recovery, the setting down on paper, for your own as well as other but friendly eyes, of what you have experienced and need now to account for and justify, or need simply to express. An act of self- awareness and discovery, but one that in its intimacy, and in the time and concentration it demands, is also an act of generous involvement with the person addressed, an avowal of personal closeness in which absence is cancelled by the most intimate presence.

The other loss is public. It is the loss of a personal record that once offered us an eye-witness account of complex happenings seen in little and from a multiplicity of places and private views.

What all this says about our attitude to time itself—how little of it we are ready to give to what we call communication and interaction with others—is another matter. This is a third loss: a loss of closeness and capacity for intimacy, that may be greater in the long run than either of the previous two.

This article first appeared in the November 2019 edition of Fryer Folios, the regular journal of the Fryer Library, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of David Malouf.

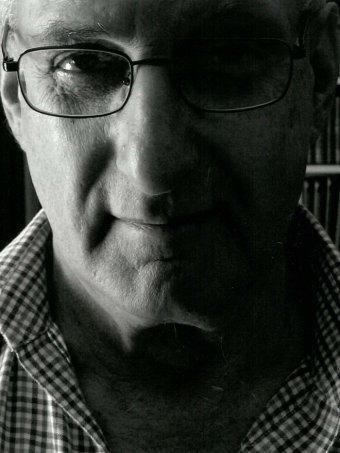

About David

David Malouf AO has published many prize-winning novels, collections of poems, short stories and essays, as well as opera libretti and a play. In 2016 he received the Australia Council Award for Lifetime Achievement in Literature. David’s most recent collection of poems, An open book was published by The University of Queensland Press in 2018.

In 2019 he donated a collection of 1745 letters written to him in the years 1960 to 2016 to add to his collection, the David Malouf Papers (UQFL163) held by the Fryer Library.