In this guest blog, Fryer intern Amanda Chambers from TAFE Queensland explores one of the more unusual items from the Fryer Library's collections, a nineteenth-century portable medical cabinet.

It is not worth-while to engage in the controversy, how far poisons are medical: since it is notorious enough, that medicines sometimes prove poisonous. - Richard Mead

It's all about the dose

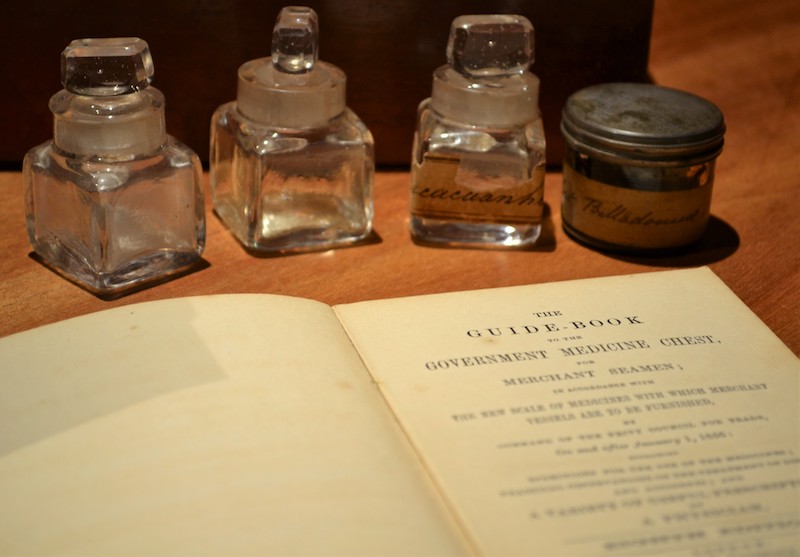

Made in or around the 1850s, S. Maw’s Portable Domestic Medical Cabinet from the Father Edward Leo Hayes Papers (UQFL2) has been a favourite piece of students and staff at the University of Queensland for many years. Aside from the beautiful craftsmanship of the box itself, the labelled bottles and first aid book provide an interesting insight into nineteenth-century medical practices, and the fine line they drew between medicine and poison.

The interesting mix of both natural and ‘scientific’ remedies found within the cabinet include:

- Alum, also known as aluminium

- Potassium Chloride

- Spirit of Sal Volatile

- Anise, also known as aniseed or star anise

- Ipecacuanha

- two different types of Sulphur

- Hydriodate Potassium

- and Belladonna, more commonly known as nightshade.

While some remedies suggested by nineteenth-century physicians do make sense today, others might lead you to wonder whether they really knew the difference between a medicine and a poison.

The miracle drug

Opium is a good example of this. Used by itself to treat a variety of illnesses in the Victorian era, it was also the foundation of the ‘miracle drug’ Laudanum, which was an opium extract mixed with alcohol such as brandy or gin. Opium, in tablet or Laudanum form, was used to treat everything from severe pain relief; to quieting crying babies and children. The overuse resulted in a high mortality rate, which led to the eventual removal of it as an available medicine. One of the missing jars from the Medical Cabinet likely originally contained opium and it may have been removed from the cabinet from this reason.

Death by sleep

Belladonna was another ‘medicine’, which was deadly unless treated with care. The garden variety of Nightshade was used to treat shingles, headaches, heartburn and induce sleep. It was also an ingredient in makeup and used as a mydriatic, a drug which dilates the pupils, in women. While it was still a risky remedy, it was not quite as toxic as the ‘deadly’ variety. It should be noted that it was being phased out (systematically destroyed) in the nineteenth century due to the dangers of the plant as an effective poison which could cause 'sleep, troubled mind', bring 'madness and kill and present death' according to an entry in Gerard’s The Herbal or General Historie of Plants (1636).

Other uses for ingredients in the cabinet included:

- using Hydriodate Potassium to treat leprosy

- mixing Spirit of Sal Volatile with horseradish and mustard seed to make a tea to treat heartburn

- inducing vomiting with Ipecacuanha powder

- drinking a tincture with Sulphur to help with gout, rheumatism and fever

- and taking Alum for sore throats, infected eyes and bruising.

How not to poison people

Some of these remedies can be found in the handbook, tucked into the lid of the cabinet titled The Guide-Book to the Government Medicine Chest for Merchant Seamen, By a Physician. This handbook was probably added to our chest later in its life, as these cabinets are much smaller than the ones issued to Merchant Ships. Another interesting source for remedies is The Medical guide, for the use of the clergy, heads of families, and practitioners in medicine and surgery which is available online through the British Library.

Perhaps the shorter average lifespan of the period played into the favour of physicians, as any lasting negative effects of the ‘medicine’ didn't necessarily have time to kick in before a natural death. In any event, the medicine cabinets of the Victorian era demonstrate how thin the line was between poison and medicine, while also making us all grateful that we don’t live in the nineteenth century!

Bibliography

Buckingham, J. 'Don't say it with Nightshades: Sentimental Botany and the Natural History of Atropa Belladonna'. In Victorian Literature and Culture, 35 (2) 2007.

Gerard, J. and Gerard, D. The Herbal or General Historie of Plants. Second edition. London: Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers, 1636.

Hamey, B. Solomon Maw, surgeon’s instrument maker. London Street Views, 2015.

Mead, R. A Mechanical Account of Poisons, in Several Essays. Third edition. London: Brindley, 1746.

Picard, L. Health and hygiene in the 19th century. The British Library, 2009.

Pieters, T. 'Poisons in the historic medicine cabinet'. In “It All Depends on the Dose”: Poisons and Medicines in European History, edited by O.P. Grell, A. Cunningham & J. Arrizabalaga. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

Reece, R. The medical guide, for the use of the clergy, heads of families, practitioners in medicine and surgery: comprising a complete practical dispensatory, and treatise on the symptoms, causes, causes, prevention, and cure, of the diseases incident to the human frame ; with the latest discoveries in medicine. Thirteenth edition. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, Paternoster-row, 1820.