To commemorate Anzac Day, we look back through collections held in our Fryer Library to examine the role that war played in the life of students and staff at The University of Queensland during the Second World War.

Dr Robinson's wars

In May 1940, Dr Frederick Robinson, a lecturer in English and German at The University of Queensland, produced a confidential document outlining a program of activity for the University during the Second World War. Robinson, who for reasons of conscience had served in the First World War in the field ambulance and as an intelligence officer rather than in a fighting capacity, had taken on responsibility for coordinating the University’s contribution to WWII.

While the emphasis of Robinson’s circular was on how to encourage enlistment and prepare students for military service, he also proposed that the University play a role in adopting the means to “clarify thought” and maintain “accurate knowledge” about the war. He insisted on vigilance to prevent “treasonable activity, deliberate opposition to the war policy and effort, and any action leading to confusion of thought, disturbance of mind and paralysis of will among members of the University.” (Frederick Walter Robinson Collection, UQFL5 Box 14). This message was directed at communists on campus, for at that stage the Communist Movement internationally was opposed to the war. In June, the Queensland University Staff Association backed Robinson’s program and wrote to the Registrar with their own suggestions on how to put the plan into effect.

Preparing for conflict

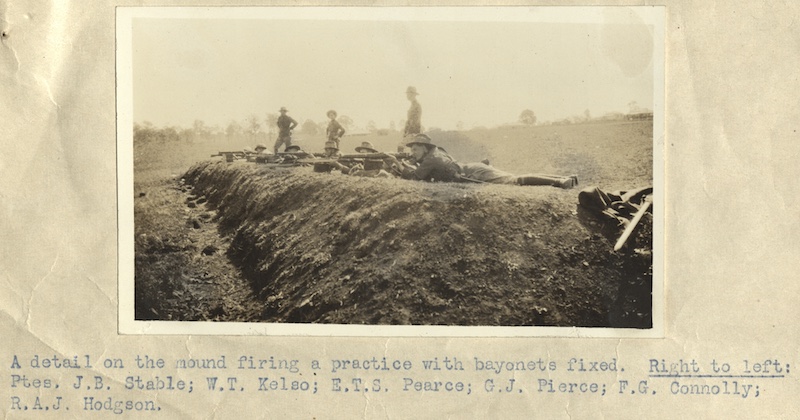

The University was already a militarised institution. In 1932, two musketry parades were held on campus during third term and there was talk of forming a militia detachment similar to the Sydney University Regiment. The student newspaper Semper Floreat assured the doubters that the commitment would be minimal, a mere one week of training at the beginning of each vacation. Based on the Sydney example, Semper opined, ‘these little social functions would be enjoyed by all: without doubt they [would be] much the same as those Survey Camps which the Engineers dream about.’ Encouraged by this apparent enthusiasm, two graduates who had become career AIF officers, Captain TP Fry and Lieutenant C Ellis, formed a University Militia Detachment in 1933. Invitations to sign up were mailed to new students with their enrolment forms.

By early 1939, even before war was declared, James Mahoney – lecturer in modern languages and then commander of the Detachment – was working closely with the Australian Government’s Department of Defence, the University administration, and the Staff Association to bolster the militarisation of the student population. Mahoney actively recruited for the Detachment with circulars enticing students with offers of pay, free uniforms, and parades “so arranged as not to interfere with lectures and classes, or athletic, social or other activities…”. Every effort was being made, Mahoney explained, “to make the training attractive to University men” (University of Queensland History Collection, UQFL458). Undergraduates who were interested in weapons were encouraged to avail themselves of the opportunity to shoot service rifles and Lewis guns. By the start of WW2, the University Detachment had grown to two platoons, comprising about 58 men.

Students as soldiers

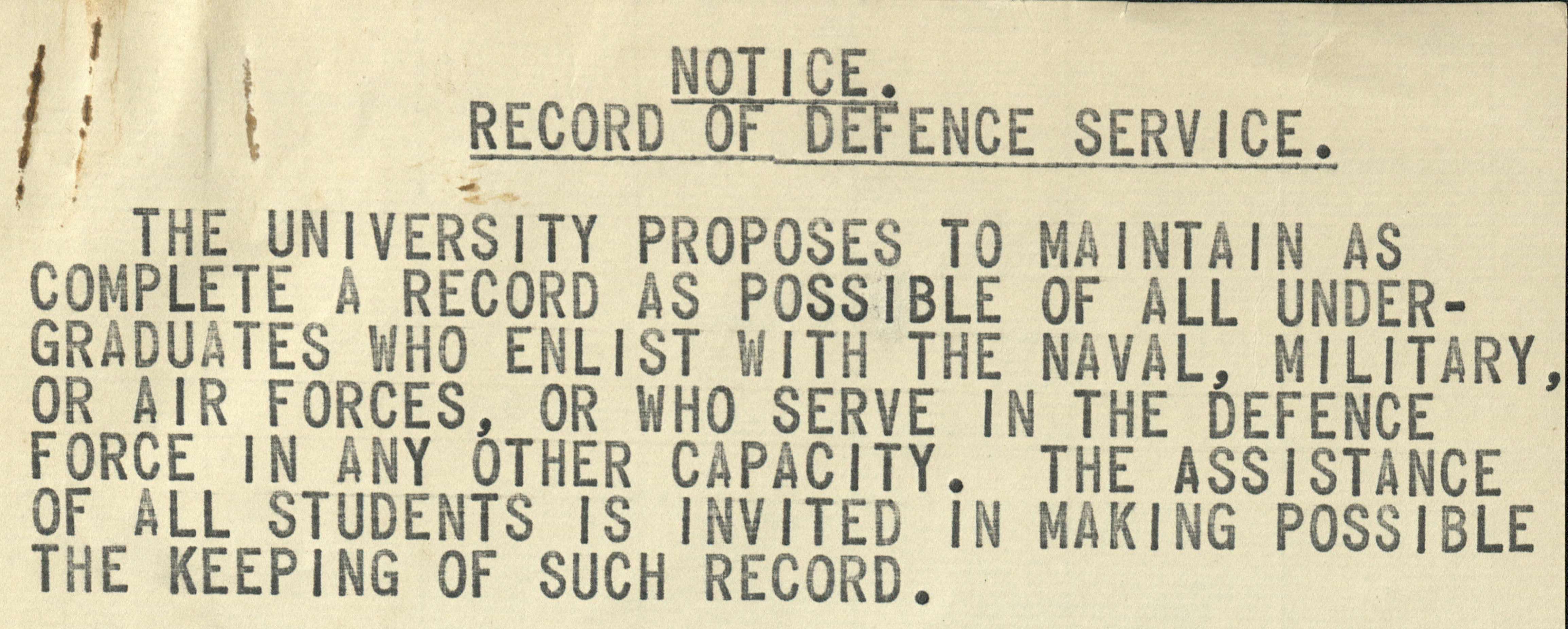

With the introduction of compulsory national military training in 1939 the university began compiling detailed lists of students eligible for call up. These were provided to Mahoney who, it is reasonable to assume, shared them with Defence. The University identified 459 eligible males aged 19 to 25, representing about half the cohort of internally-enrolled male students.

By August 1940 the university was working closely with military authorities to arrange compulsory training for all remaining eligibles. Notices were posted on campus calling on students to supply details of their service according to three categories: those who had definitely enlisted, those who had enrolled for service but had not yet been called up, and those allocated to war service in other capacities. In 1942 a census of undergraduates was taken to ascertain their physical and military capabilities. Weekly first-aid classes and field exercises were introduced to improve war readiness.

The recruiting fervour of Mahony, Robinson and other University authorities reaped its rewards. From 1939 to 1945 hundreds of University of Queensland students went to war. Before the conflict was over, the University’s list makers were at work again, compiling rolls of the dead. By 6 March 1946 their list included 83 University men known to have been killed or died while in service. But as the authorities acknowledged, this roll was a work in progress.

Commemorating war at the University

In the post-war years, Robinson again became engrossed in war-related duties, this time as a prominent member of the University’s War Memorial Committee. Charged with the responsibility of selecting a suitable inscription for the memorial, he chose lines from John Milton’s play Samson Agonistes:

Nothing is here for tears, nothing to wail

Or knock the breast, no weakness, no contempt,

Dispraise, or blame, nothing but well and fair,

And what may quiet us in a death so noble.

While the nobility of the University’s war deaths may be questioned, not so the men who died or the University’s commitment to the cause of war.