On Australian South Sea Islanders Recognition Day, we reflect on the history and survival of islander people and culture as well as the important contribution Australian South Sea Islanders have made to Queensland.

The Fryer Library cares for significant collections that can contribute to our national reconciliation journey and truth-telling. Among these collections are items relating to the history of the Queensland labour trade, which benefitted the state economically, and reveal aspects of the practice known as ‘blackbirding’.

'Blackbirding', or slave trafficking, involved the kidnapping or questionable recruitment of people for their labour. Between 1863 and 1904, approximately 55,000 to 62,500 South Sea Islanders were taken to Australia to serve as labourers on sugar cane and cotton farms in northern New South Wales and Queensland. They also worked in the pastoral industry and in North Queensland maritime industries. These mostly-young men and women came from over 80 different islands, including:

- Vanuatu (previously New Hebrides)

- The Solomon Islands

- New Caledonia

- Papua New Guinea

- Kiribati

- Fiji and Tuvalu

The first South Sea Islanders to be transported to Australia, in the 1860s, had no labour contracts or laws to protect them from mistreatment and exploitation by their employers. In 1868 the Polynesian Labourers Act was passed to control the trafficking of South Sea Islanders into Queensland through an indentured labour system. Under this Act, labourers signed three-year contracts which stipulated minimal wage payments and conditions of employment. Working days in the sugar fields and over the sugar boilers were long, hot and hard. The average day of toil was ten hours, with no work on Sundays. Labourers customarily started at 6.00am and in the height of the crushing season, observed James Hope, they would ‘toil on late at night over the steaming tache’ in exchange for a little extra tea, bread and butter, or tobacco…' (Hope, p.111).

The Fryer collections also contain important items that reflect the resilience and culture of the South Sea Islander community in Australia. By presenting some of these items we seek to contribute to truth-telling and honour the community on Australian South Sea Islanders Recognition Day.

While this digital story includes items that reveal aspects of this history, the personal stories are the lived experience of the South Sea Islander community and are theirs to tell. As a custodian of this material, the Library seeks to build deeper connections with the Australian South Sea Islander community to raise awareness of these collections and engage. Through work such as this, we hope to connect with Australian South Sea Islander peoples and work with the community to facilitate access to these collections. We invite the community to share stories, lend your voice to future projects, and contact us about co-creating content that contributes to understanding and truth-telling.

Recent history and the fight for recognition

Recognition of the Australian South Sea Islander community and their essential role in the Australian sugar and cotton industries took a long time.

Descendants of the labourers have been fighting, advocating, and campaigning for recognition since the 1970s.

On 25 August 1994, the Australian Government formally recognised Australian South Sea Islanders as a distinct ethnic group in Australia with a distinctive culture and history. The Government also acknowledged the injustices of the indentured labour system, the hardship endured by the South Sea Islanders and their descendants, and their contribution to the economy, history, and culture of the country. The anniversary of this event is commonly referred to as Australian South Sea Islander Recognition Day. This recognition came after the 1992 Call for Recognition Report by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. The report urged governments through numerous recommendations to act and improve the access and equity experienced by this community, noting it had been disadvantaged significantly. On 7 September 2000, the Queensland Government formally acknowledged the contribution of the South Sea Islander community.

Although formal recognition has been provided, the quest for practical recognition is ongoing and the descendants of the South Sea Islanders brought to Australia during this period and many in the wider population continue to campaign for this.

One contemporary example of a project that aims to provide practical recognition and respect for the contribution of the South Sea Islander community has involved volunteers working to commemorate unmarked graves in Mackay.

There has also been a push within the community to reconsider who and what is commemorated within Australia. Monuments like the statue of Robert Towns located in the main street of Townsville have been seen as celebrating a man whose legacy is associated with blackbirding and fails to represent the whole truth of our history. In 2021, the Mayor of Bundaberg offered an historic formal apology to the South Sea Islander community for the practice of blackbirding in the region.

These practical examples, together with the primary and secondary source material presented here, reflect the strength and resilience of the Australian South Sea Islander community, their proud heritage and legacy, and the battle to tell the entire truth of history.

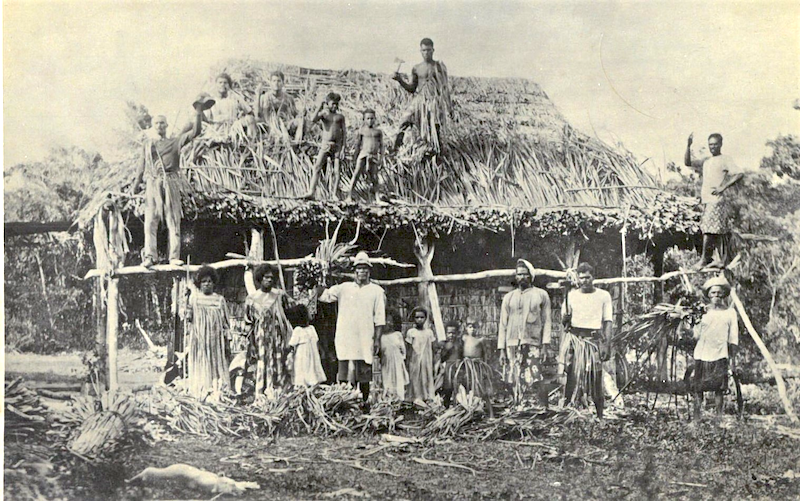

Contrasting conditions

The photographs below show what life would have been like in an idyllic village such as in New Caledonia at the time blackbirding recruiters arrived. Compare these images (Ralph Cilento Papers, UQFL44, Box 39) with the those showing what conditions were like working on sugar cane plantations in Queensland (Queensland Agricultural Journal, Volume 1 Part 4, October 1897, p. 296); (Queensland Agricultural Journal, Volume 1, Part 3, September 1897, p.246).

Transporting labourers

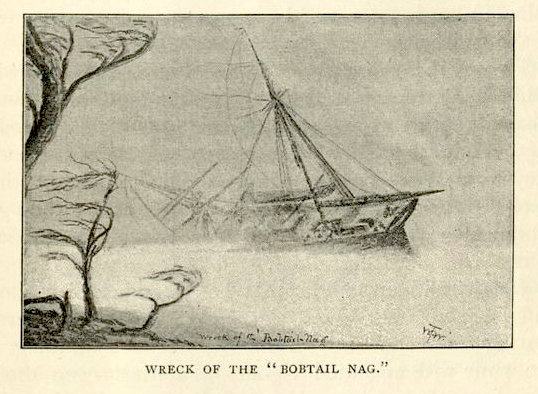

The Bobtail Nag was a 178-ton leaky schooner licensed by the Governor of Queensland to carry up to 123 indentured labourers per voyage between the South Sea Islands and the ports of Queensland. On 7 June 1875, the Nag’s crew, under the command of Captain David Murray, weighed anchor in Moreton Bay, offloaded the pilot, and set sail with 28 Islanders aboard, bound for their home islands in present-day Vanuatu. Twenty of the 28 were from the island of Gaua (or Ganna). All had completed their three-year work contracts on the farms of Southeast Queensland.

As the labourers were delivered to their destinations over the next few weeks, the Nag began to take on new recruits, first from the islands of Vanuatu and then from the Solomon Islands to the north-west. After a successful sweep through the Solomons, the Nag travelled to Port Denison in North Queensland. Three Islanders died on this leg of the journey. After delivering five recruits to employers in Bowen, the vessel sailed for Brisbane. Another Islander died as the Nag made its way down the coast. On 27 and 28 September, 84 Islanders were landed in the colonial capital, and on 14 October, 13 were transferred to another vessel, the Lucy Adelaide.

The Bobtail Nag then headed back to the Solomons to fill its bunks again. When Murray finally ordered the crew to turn for home on 1 December, it was carrying 102 Islanders, most of them from Malaita, with at least one woman among them. Upon dropping anchor in the Brisbane River on 24 December, 98 recruits were passed fit in the muster. Two men had died on the return voyage, and one had succumbed to burns sustained when his tent caught fire during quarantine on Peel Island. One man remained in quarantine, recovering from illness.

Of the 177 Islanders known to have reached the Australian mainland from the 1875 voyage of the Bobtail Nag, the names of only 14 are known to us from government records. They were Cuneya, Owanni, Vassa, Ellemanna, Siminee, Foorea, Foota, Gwena, Kabao Tow, Kwina, Logui, Soo Liboo, Tarsoo and Lconen. Vassa came from Santa Isabel Island, the others from Malaita.

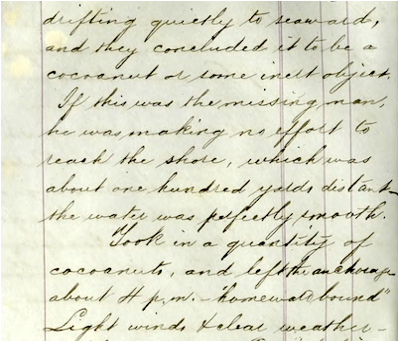

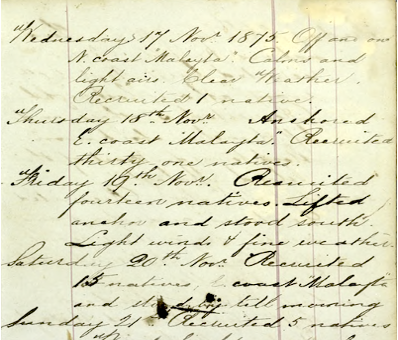

The owners of the Bobtail Nag did well from the 1875 voyage, with a known total of 177 South Sea Islanders delivered to employers, fit for service. The diary of the voyage indicates most of the Islanders came from Malaita (spelled Malayta in the diary). Its pages tell us that 75 people were recruited from the island in only a few days – 17-25 November. The diary also records the deaths of seven people, including two in horrible circumstances on one day, Tuesday 24 August. For a day-by-day account of the 1875 journey, read the original journal of the voyage held by Fryer Library and available online.

Defiance!

Throughout the Melanesian labour trafficking era, both supporters and opponents of the practice made much of the claim that South Sea Islanders were happy with their lot. Writing in 1872, sugar farmer Charles H. Eden claimed ‘his’ 20 South Sea islanders would work conscientiously without supervision. ‘I found them docile, laborious, light-hearted, good-tempered, and most faithful and affectionate,’ he wrote. (My Wife and I in Queensland, p.327) The Reverend Alex C. Smith, a pro-trafficking propagandist employed by the Presbyterian Church, was also adamant that amongst the South Sea Islanders on the plantations, there was ‘a general air of contentment, and often of placid happiness.’ (The Kanaka Labour Question, p. 23)

Open resistance, of course, was difficult. When it occurred, repercussions could be severe. But it did occur.

The case of the Westbrook Eight

On the morning of 4 June 1872, eight South Sea Islanders appeared at the Toowoomba home of Police Magistrate Gilbert Eliott. Their names were Emile, Twallah, Appleuse, Joe, Wah-woo-an, Johnny, Billy and Misktha. The index to South Sea Islander records compiled by the Queensland State Archives indicates that at least four of them were from the island of Lifou. Given the evident bond between them, it is plausible they all were.

The men had walked 19 kilometres from Westbrook Pastoral Station, where they were employed under contract as general labourers. They had come to Magistrate Eliott seeking justice. They had left the station together, they said, after the station superintendent, Donald Ross, had refused their demands and, in their opinion, discharged them from employment by telling them to find their own way back to Brisbane. They wanted Eliott to issue a direction allowing them to return to service.

According to Eliott’s report, the men were aggrieved because Ross had refused three times to provide them with knives to eat their meat. In Ross’s account, however, the grievances were more complex, indicating a deeper hostility to the employment arrangements and possibly to Ross himself. According to the superintendent, the men had refused to work when he tried to separate them. After he relented and sent them as a group to a location eight miles from the Head Station, they again refused to work, on this occasion demanding to be issued with blankets. Ross claimed he offered to supply blankets as soon as possible, but the men would not back down. He threatened to have them gaoled. When this failed to break their resolve, he claimed he ordered them back to the Head Station. This, he told the Magistrate, was the last he saw of them.

When Eliott informed Ross the men were in Toowoomba, Ross demanded they be charged with absconding. Eliott initially resisted, arguing that the men had not absconded but had come to town to lodge a complaint. However, when Eliott took Ross to see the men and attempted to mediate a settlement whereby Ross would meet all their demands in exchange for a return to work, the men refused. ‘No, gaol very good place,’ they responded. Evidently, at some point between their arrival at Eliott’s home and the meeting with Ross, the men’s attitude had hardened.

Believing his options exhausted, Eliott formally charged the men with ‘absenting themselves from their hired service and refusing to return.’ In court that afternoon, each man reiterated his refusal to cooperate. The inevitable convictions were recorded. Billy, regarded as the leader of the group, was sentenced to three months’ prison with hard labour. The other seven were handed sentences of one month imprisonment with hard labour. Eliott ordered that all eight be returned to Westbrook at the completion of their sentences.

The remarkable defiance, solidarity and dignity demonstrated by the Westbrook Eight belies the racist imagery of the compliant and supine servant. Their stand also speaks to the harsh reality of life as an indentured labourer, where gaol with hard labour was sometimes preferable to employment servitude.

Contemporary voices

The second generation of Australian South Sea islanders has also played a significant role in reviving the culture. Through activism and writing, they have kept an awareness of the place of Australian South Sea Islanders in this country.

Faith Bandler (1918-2015) is one such activist and writer. In her novel, Wacvie, she writes an account of her father's life. Wacvie Peter Mussingkon was from Biap village, Ambrym, in Vanuatu. He had been kidnapped from this village and sold as a slave to a sugar plantation in Queensland in 1883 when he was just 12 years old. Wacvie was published in 1977, at a time when Bandler, a well-known activist and supporter of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders, focused her attention on obtaining recognition and special benefits for the descendants of her father’s people. In 1974, Bandler was instrumental in the formation of the Australian South Sea Islanders United Council.

Biographical novels such as Bandler’s provide valuable written testimonies, while also contributing to a revival of Australian South Sea Islander culture in the 1970s as descendants living in Australia sought to reconnect with their home islands and ancestry.

In the introduction to Wacvie, Bandler explains that she wrote the book after her return from Ambrym Island in Vanuatu, where her father had been abducted. Her purpose was to tell his story and thus give a voice to all those who had been “enslaved”. She also intended to reveal a part of Australia’s history that had been erased from people’s memory.

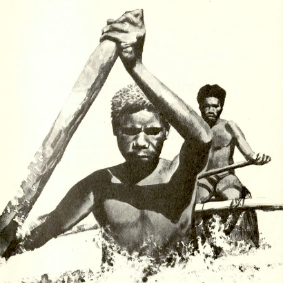

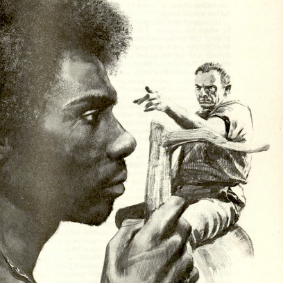

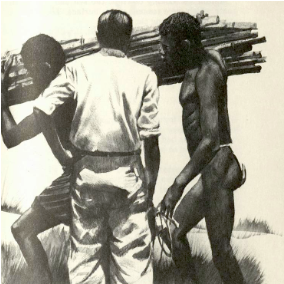

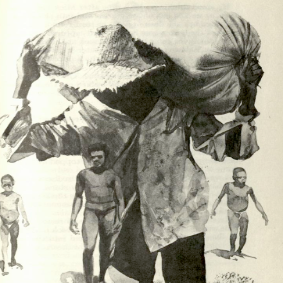

Bandler also wrote Marani in Australia with Len Fox. It tells the story of Marani, a young boy living in an island village until his father is kidnapped by blackbirders and taken to Queensland to work on a sugar plantation. It follows Murani’s journey in search of his father Tarua. It sees Murani working in the cane fields until he could escape the punishing conditions, and other obstacles he encountered in his search to find his father. The powerful illustrations featured throughout the book, drawn by Len Fox, show the extreme conditions of working for white plantation owners in Queensland.

Len Fox illustrations

Bandler's book, Mariani in Australia.

Bandler's book, Mariani in Australia.

Bandler's book, Mariani in Australia.

Bandler's book, Mariani in Australia.

References

- Bandler, Faith (1977) Wacvie. Adelaide: Rigby.

- Bandler, Faith & Fox, Len (1980) Marani in Australia. Norwood: Rigby.

- Eden, Charles (1872) My wife and I in Queensland: an eight years' experience in the above colony, with some account of Polynesian labour. England: Longmans.

- Hope, James (1872) In Quest of Coolies. London: King.

- Murray, David Diary of the cruise of the Bobtail Nag to the South Seas, 1875 Captain David Murray, F537, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

- Queensland Agricultural Journal, Volume 1, Part 3, September 1897, p.246.

- Queensland Agricultural Journal, Volume 1 Part 4, October 1897, p. 296.

- Raphael Cilento Papers, UQFL44, Box, 39, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

- Smith, Alex C. (1892) The Kanaka Labour Question with special reference to missionary efforts in the plantations of Queensland. Brisbane: Muir and Morcom.

Are you from an Indigenous Knowledge Centre, of South Sea Islander heritage, or involved in community leadership? Would you like to help add more to this story? We would love to hear from you. Please contact the Fryer Library by email at fryer@library.uq.edu.au and we will get in contact with you.

This digital story is dedicated to the men, women, and families who continue to fight for recognition and truth-telling. We also dedicate this story to the memory of our dear colleague Naomi Franks, a proud Aboriginal and South Sea Islander woman, who has been a part of this project from the beginning and whose voice and experience have guided the development of this story.