What to read when you're going to war: the William A. Amiet papers

Jim Cleary discovered the papers of William Albert Amiet while working on the Australian Reading Experience Database in 2009. In this guest blog post, he shares the insights they give into the reading habits of a young Brisbane professional heading to war.

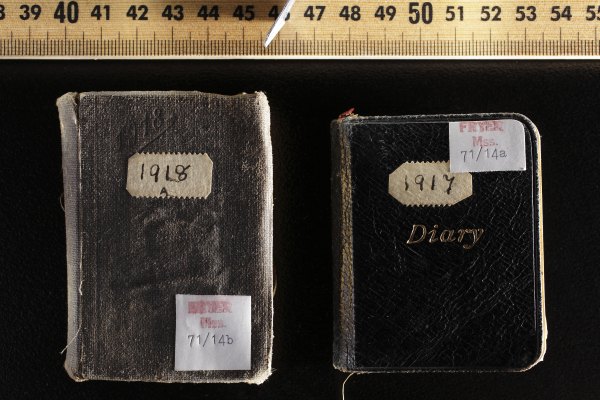

The papers of William Amiet (1890-1959) were one of the most interesting collections of private papers I came across, including 56 diaries and seven bound volumes of news clippings, the latter since published in book form. The diaries are the size of cigarette packs and require a magnifying glass to read them. The entries are necessarily brief, systematically recording books read, bookshop orders, newspaper/magazine subscriptions, income and expenditure as well as day to day activities. Unfortunately, Amiet systematically discarded his vast correspondence at intervals throughout his life and the family papers in Victoria were destroyed in 1984.

The Amiet papers are significant because they shed light on the world of a brilliant Edwardian scholar growing up in Victoria prior to the Great War, the endeavours of a Christian moral reformer in the Queensland bush, recreational patterns in Brisbane at the outbreak of war and the reading history of a barrister before and during his participation in the Great War.

Amiet had an idyllic childhood on the family farm near Geelong, helping with farmwork and attending a state school. The Amiets were a deeply religious Presbyterian family with Sunday church services and Bible study classes. Amiet's diaries reveal he read avidly, devouring the classics of English literature, historical romances, Sherlock Holmes mysteries and his grandmother's magazines such as Good Words, The Royal Magazine and The Windsor Magazine. He also found time for Adam Lindsay Gordon and the family would read Steele Rudd and the Bible aloud of an evening. Even before he attended the University of Melbourne in 1908, Amiet subscribed to Walter Murdoch's modern language review, The Trident, written in English, French and German. Amiet was a member of one of the last cohorts into Arts at the University of Melbourne for whom Greek and Latin were compulsory. He gained double firsts and was the top honours student of his year.

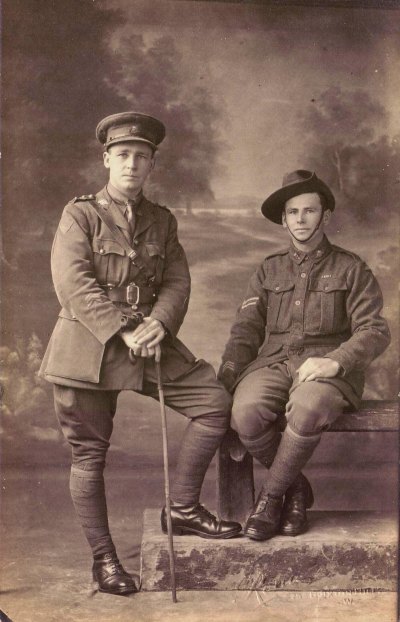

After a brief period teaching and engaging in mission work in the poorer suburbs of Melbourne, Amiet accepted a position as a YMCA secretary at Mount Morgan, Queensland dedicated to the provision of social and recreational activities for railway navvies and 'soul winning' for Christ. The diaries provide a fascinating insight into bush print culture and recreational activity in a navvies camp. This was to be a test of Amiet's commitment to the Christian ministry. His crisis of faith came to a head in September 1912 and as a consequence, he left YMCA employment in 1913. Amiet became a schoolteacher at Maryborough Boys Grammar School and in early 1914 made the fateful decision to become a barrister. He resolved to complete his legal studies before joining the First AIF and thereby missed Gallipoli and the battle of the Somme. Only about a quarter of the first 30,000 recruits in 1914 ever saw Australia again. By the time he went to war Amiet was tending towards agnosticism but he continued to attend church and subscribe to The Queensland Young Man, the local YMCA magazine, until he left Australia in 1916.

The diaries provide a treasure of insights into the social life of a young professional in Brisbane in 1914-1915. Amiet resided in a guest house for both sexes, Mon Repos, on Gregory Terrace. There were long walks and horse rides all over Brisbane including One Tree Hill. Sometimes there were film outings to the Strand at the corner of Queen and Albert Streets. Amiet discussed the war with male friends as a steady stream of acquaintances joined the AIF. A move to the suburb of West End saw him reading Byron in the park as the band played and Lucian in the Greek that night. A poem he wrote on Belgium was published for 15/- but he failed to win the Daily Mail poetry competition. On 7th August 1915, Amiet bought a book on the 'Belgian outrages', possibly the Bryce Report, and this may have been the turning point that led him to volunteer. On 10 October 1915 Amiet wired home that he was going to war after his legal examinations in 1916.

Despite the travails of war, Amiet managed to maintain his diaries with their detailed record of his reading, military experience and travels in England over the next three years. They represent a unique record of a wartime barrister and soldier who can stand alongside others in that minority of intellectual "sensitives", in Serle's words, that included the future lexicographer Eric Partridge, the novelist Martin Boyd and the educationalist Kenneth Stewart Cunningham. A few vignettes will illustrate the richness of the diaries. Amiet spent nearly six months at the No. 6 Officer Training Battalion, Magdalen College, Oxford University and he made the most of the opportunity to experience the wide array of cultural activities that even a wartime university offered. Amiet wasted no time in visiting Mudie's Library in London and Blackwell's Bookshop in Oxford where he bought language books. He went to at least ten public lectures, mainly by Oxford professors, ranging from Greek sculpture to contemporary politics. Amiet participated in the Oxford Union Society debate in favour of an Imperial Parliament; witnessed May Day singing of Latin hymns in Magdalen Tower and visited the gardens of Blenheim Palace.

On the 1st August 1918, Amiet's commission as an officer came through and on the 19th he sailed for France. There was time for a few days leave and he headed for Stratford on Avon, visiting Shakespeare's birthplace. He noted the signatures on the wall: Scott, Byron, Carlyle and Thackeray. That evening 'After supper we all went out to the Avon in punts. Glorious. Our room called 'Rosalind.'' Amiet thoroughly upsets our preconceptions about highbrow/lowbrow and the literary canon the next day: "Saw Marie Corelli's home (covered in flowers, music room beside).' As in previous military campaigns, the reading of poetry becomes a more frequent occurrence. He read most of the poems of Scott and Kingsley as well as the Scottish preacher David Macrae's A Pennyworth of Parodies (1896).

On the 20th September Amiet received notification that his unit was to prepare for battle. Over the next few days, he read Vergil's Aeneid Book 11 and Macaulay's Horatius. His last recorded reading experience before the battle of Bellicourt 2-4 October is Macaulay's essay on Lord Clive 'His name stands high on the roll of conquerors. But it is found in a better list, in the list of those who have done and suffered much for the happiness of mankind. To the warrior, history will assign a place in the same rank with Lucullus and Trajan.' He also managed to finish the last 200 lines of Virgil.

Amiet went over at 6.05 am on the 3rd October as part of the 7th Brigade's assault on the Beaurevoir Line, confronting two and in some cases three defensive trenches, over fifty machine guns and pillboxes. Wounded by shrapnel Amiet was repatriated to England; his war was over although he did not see Australia again until November 1919.